Goods delivery by automated or even autonomous drones? What we know at best as a vision from science fiction films could soon become everyday life. At least when it comes to Amazon, UPS, Mercedes Benz and DHL. What are the challenges, what is legally permitted in Germany – especially with regard to airspace security? And which logistical approaches of the service providers are already known? A summary.

Duocopter, Tricopter, Quadcopter, Hexacopter and Octocopter: all these drone variants fly – but these technical terms are not as widespread as the collective term air drone or simply drone. In general, it combines all types of so-called multicopters. The main difference is simply the number of propellers and engines used. Another term frequently heard in this context is the ‘Unmanned Arial Vehicle’ (UAV). It excludes, in contrast to the term ‘drone’, objects on water and on land. Another common term: Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS). These are explicitly aircraft which, unlike autonomous flying objects, do not take to the air without remote control (automated flight control).

- A duocopter has two horizontal rotors and motors (very rare).

- A tricopter has three horizontal rotors and motors (very rare).

- A quadcopter has four horizontal rotors and motors (a common setup).

- A hexacopter has six horizontal rotors and motors.

- An Octocopter has eight horizontal rotors and motors.

Multicopters and the laws of physics

The more mass one wants to move, the more energy must be applied. Since the energy for a flight comes from an energy storage device placed in the flying drone, which generally is subject to a lack of space, one quickly reaches its limits. More energy means that a larger and consequently heavier battery must be used, which in turn increases the mass to be moved. If the drone is used to transport goods, the payload must also be considered, which increases the weight further. There are currently three conceivable variants:

- An additional compartment is attached to the drone base in which goods can be stowed.

- A net is attached to the drone base in which the goods to be transported lie.

- A bag is attached to the bottom of the drone, which is delivered at its destination by parachute (see Amazon example).

Note: Flying drones with a payload of up to four kilograms can currently (2017) achieve a flight time of only 20-30 minutes.

The areas of application of the Multicopter are nevertheless diverse. So they serve as a hobby object for flying, filming, photography and in some cases racing. Or they are used in the professional sector. The flying drones have already established themselves in the following business areas.

- Research

- Forestry and agriculture

- Industrial maintenance

- Surveying technology / terrestrial surveying

- Safeguarding the population with the aid of the police, fire brigades or disaster relief organisation

- Use in logistics (see test phases)

- Disaster relief

- Border guard

- Movie industry

The legal situation in Germany

Essential regulations: Drone Ordinance

1. Mandatory identification: All aircraft models and unmanned aerial vehicle systems with a take-off mass of more than 0.25 kilograms must in future be marked so that the owner can be quickly identified in the event of damage. The identification is ensured by means of a placard with the name and address of the owner.

2. Proof of proficiency: In future, proof of proficiency will be required for the operation of model aircraft and unmanned aerial vehicle systems weighing two kilograms or more. The proof is provided by (a) valid pilot licence, b) Certificate after examination by a body recognised by the Luftfahrt-Bundesamt (also possible online), minimum age: 16 years c) Certificate after briefing by an aviation sports club (applies only to model aircraft), minimum age 14 years The certificates are valid for five years. No proof of knowledge is required for operation on model flying sites.

3. Freedom from permission: in principle, no permission is required for the operation of model aircraft and unmanned aerial vehicle systems with a total mass of less than five kilograms. Operation by public authorities is generally not subject to authorisation if it is carried out for the fulfilment of their tasks, as is operation by organisations with security tasks, for example, fire brigades, the German Federal Agency for Technical Relief (THW), the German Red Cross (DRK) etc.

4. Permission requirement: a permit is required for the operation of model aircraft and unmanned aerial vehicle systems weighing more than five kilograms and for night operations. This is issued by the state aviation authorities.

5. Opportunities for future technologies: Until now, commercial users needed a permit to operate unmanned aerial systems – regardless of weight. In future, the operation of unmanned aerial vehicle systems weighing less than five kilograms will in principle no longer require a permit. In addition, the existing general ban on operating beyond line of sight will be lifted. In future, state aviation authorities will be able to permit this for devices weighing five kilograms or more.

6. Operating ban: an operating ban will in future apply to model aircraft and unmanned aerial vehicles

- beyond line of sight for equipment under five kilograms;

- in and above sensitive areas, e.g. places of action of police and rescue services, hospitals, crowds of people, plants and facilities such as prisons or industrial plants, federal or state authorities, nature reserves;

- over certain traffic routes;

- in control areas of airports (including arrival and departure areas of airports);

- at flight altitudes above 100 metres above ground, unless the operation takes place on a terrain for which a general permit for the ascent of model aircraft has been issued and for which a supervisor has been appointed, or unless it is a multicopter, the controller holds a valid pilot’s licence or has a certificate of proficiency;

- over residential property if the take-off mass of the device exceeds 0.25 kilograms or if the device or its equipment is capable of receiving, transmitting or recording optical, acoustic or radio signals. Exception: The person whose rights are affected by the operation above the respective residential property expressly agrees to the overflight;

- above 25 kilograms (applies only to ‘Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Systems’).

7. Ausweichpflicht: Unbemannte Luftfahrtsysteme und Flugmodelle sind verpflichtet, bemannten Luftfahrzeugen und unbemannten Freiballonen auszuweichen.

8. Use of video goggles: Flights using video goggles are permitted if they take place up to a height of 30 metres and the device does not weigh more than 0.25 kilograms or if another person constantly observes it in line of sight and is able to alert the pilot to any danger. This is considered to be operating within the range of vision of the controller.

Wichtig: Die zuständige Behörde kann Ausnahmen von den Verboten zulassen, wenn der Betrieb keine Gefahr für die Sicherheit des Luftverkehrs oder die öffentliche Sicherheit oder Ordnung, insbesondere eine Verletzung der Vorschriften über den Datenschutz und über den Naturschutz darstellt und der Schutz vor Fluglärm angemessen berücksichtigt ist. An objective safety assessment can be submitted to the regulatory authority, particularly in the case of planned beyond-line-of-sight operations.

The ordinance was announced in the ‘Bundesgesetztblatt’ on 6 April 2017 and came into force on 7 April. The regulations concerning the identification obligation and the obligation to provide proof of proficiency will apply from 1 October 2017.

We do not believe that drones will fly to the front door or the individual balcony in the near future, but rather in fixed corridors, for example from the warehouse to the distribution centre. The last mile will still be completed by car or bicycle.

Jörg Lamprecht, CEO of Dedrone GmbH in Kassel

Drones in logistics practice

There is still a long way to go before mass delivery by flying drone. Even if the idea behind it is relatively easy to implement: Take a drone, hang a parcel under it and send it directly to the customer. The associated responsibility of the operator or CEP service provider is all the more weighty. On the one hand, the legislator must take legal account of the delivery of goods by multicopter in air traffic control matters and help to shape the necessary infrastructure. On the other hand, companies must continuously develop relevant technologies. This also includes the networking of the available infrastructure; including the legal safety regulations (data protection, air traffic control, insurance cover for property and personal damage). A long-term and costly undertaking. Nevertheless, some companies like UPS, Amazon, DHL and Mercedes are already experimenting with these flying objects.

UPS

For less densely populated areas, UPS has been working for some time on a solution that combines current transport solutions (vans) with flying drones. In the future, the transport vehicles will be equipped with drones to save the driver detours. In February 2017, the first successful tests were announced: The flying drone was loaded by the driver of the transporter and delivered the test packages autonomously to private households. The drone returned to the vehicle on its own after delivery; while the deliverer continued his route in the vicinity and delivered other packages (see video). The maximum flight time is said to have been 30 minutes. The load capacity is specified to be 4.5 kilograms. UPS claims to have drastically reduced its travel cost by providing this additional support in their fulfilment processes. According to the company, saving just one mile per deliverer per day over a year can reduce costs by up to 42 million euros.

Amazon

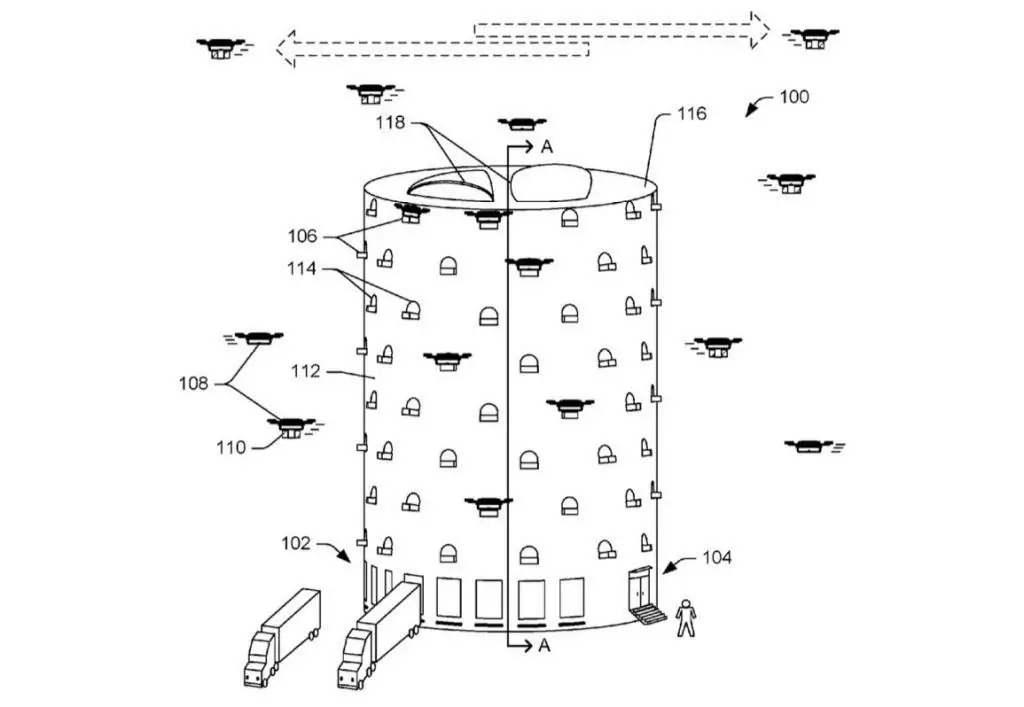

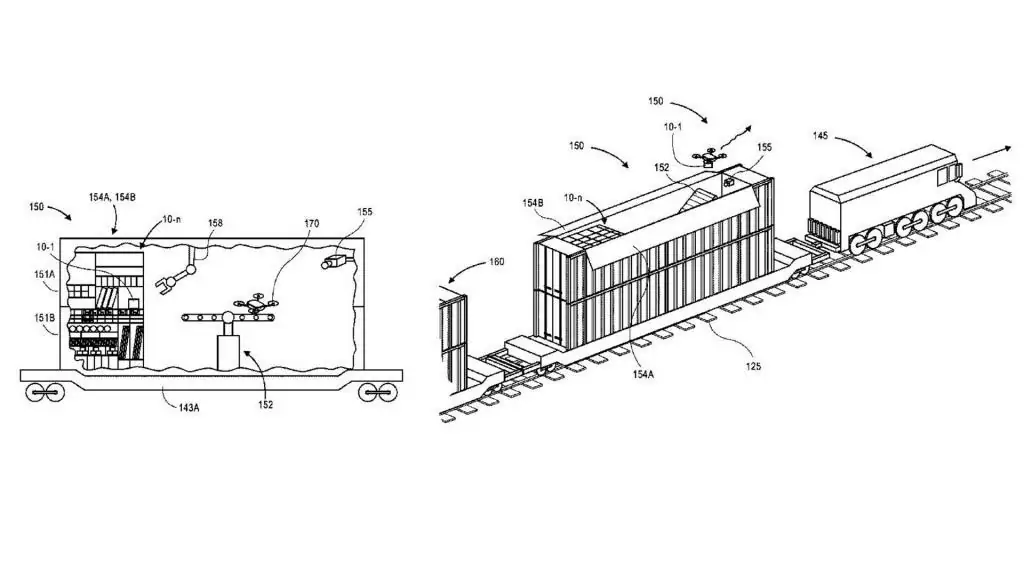

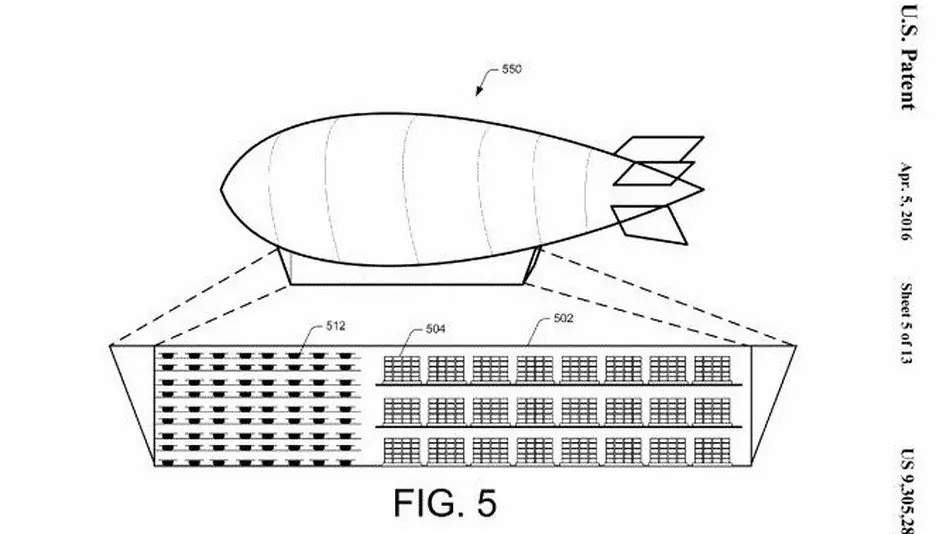

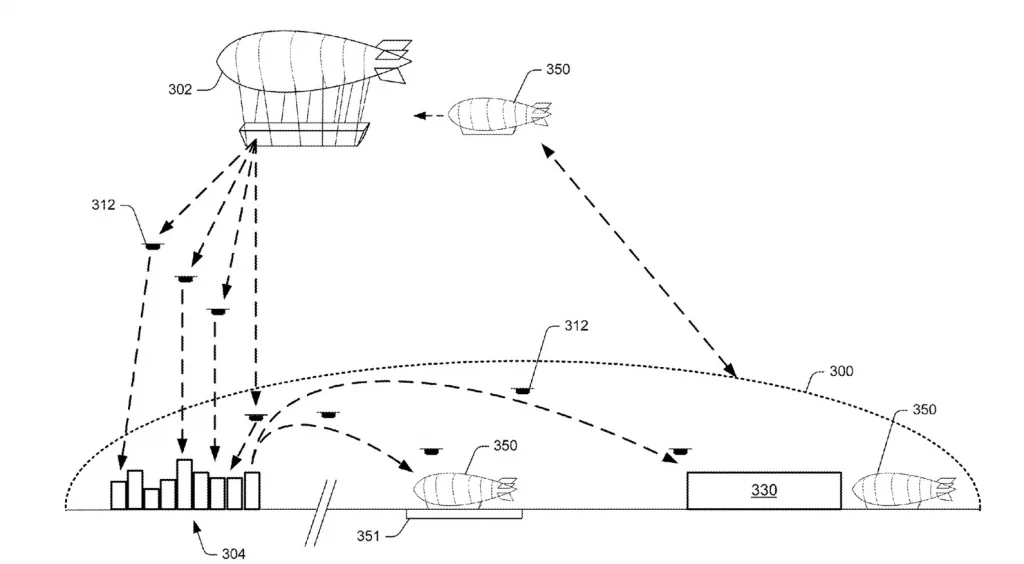

Amazon is also very interested in making its goods available to customers by air, but takes a different approach. The goods are to be delivered directly from a ‘flying distribution centre’ to the customer. A patent shows for this purpose, futuristic-looking airships that hover at an altitude of up to 13,700 meters above the ground. A swarm of drones will then bring the goods quickly and directly to the customers. At least this is the plan of the US company. But there are also plans to raise drones directly from a conventional distribution center – in the centre of a city. In addition, a concept is known in which Amazon, similar to UPS, uses a classic means of transport as a basis: the train (see patent illustration). Moreover, the service should not be limited to consumer goods. Moreover, the service is not intended to be limited to consumer goods. Amazon plans to use a flying drone to deliver food or even ready-prepared meals.

Even if the airships are still dreams of the future, of course: Delivery by drone without a ‘mother ship’ has long been an topic of discussion for the US corporation as well. The Amazon drones of ‘Prime-Air’ are to take over the last mile to the customer before the airships do. The outstanding feature: According to the company, the Amazon drone will consume much less energy than conventional drones. The delivery drones simply drop the parcel over the destination; the goods hang on a parachute. The drop means that fewer take-offs and landings are required.

DHL

In Germany, too, work is already underway on delivery using flying objects. DHL has been researching on the ‘Paketkopter’ since 2013 and has presented its results in a transparent way since then. DHL will initially concentrate on areas that are difficult to access, such as the North Sea islands or locations that are difficult to reach due to mountain ranges. The latter test phase was realized and successfully tested in 2016 using a specially developed packing station, the Parcelcopter SkyPort (see video).

- At the Winklmoosalm, private customers were able to arrange for their delivery during a three-month test phase and by placing their shipments in the Skyport.

- The parcel copter inside the Skyport took over the shipment automatically (see video) and delivered it autonomously to the recipient.

A total of 130 autonomous loading and unloading operations were carried out within the project period. From the valley to the alpine pasture, 500 metres of altitude difference per route and a distance of eight kilometres were covered. The payload was up to two kilograms and the cruising speed is stated as 70 kilometres per hour (see diagram).

Worth mentioning: the development stages of the three pilot projects. The payload in 2013 and 2014 was still limited to 1.2 kilograms. In 2016, two kilograms could already be transported. In addition, a top speed of only 43 kilometres per hour was reached at the beginning (in 2016, as mentioned, it was 70 kilometres per hour). It is worth mentioning that in 2013 and 2014 a quadcopter was used; since 2016 DHL has been using a tilting wing aircraft. It has a wing span of almost two metres, a length of 2.2 metres and weighs 14 kilograms without goods. A conventional quad copter cannot keep up with this, of course. The special feature of the tilting wing aircraft are the wings, which are tilted around the transverse axis of the aircraft for take-off and landing in order to change the direction of thrust of the two electric engines.

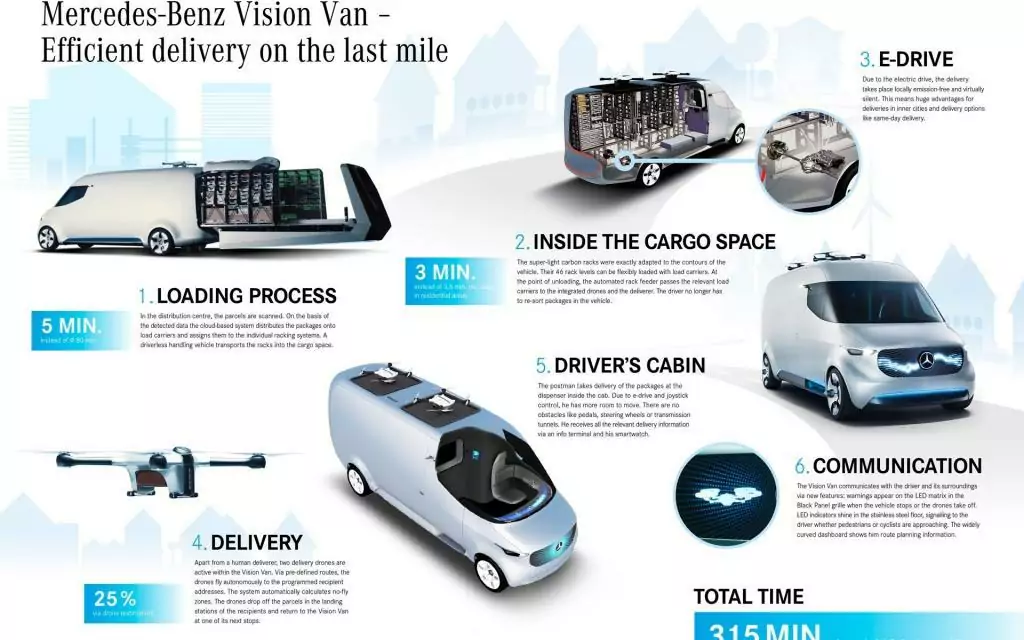

Mercedes Benz

The car manufacturer Mercedes Benz is also testing the use of its vans paired with drone technology. On the one hand, the company has been working for some time with the US company Matternet (see video), and on the other hand, the ‘Vision Van’ project has been developing a transporter study for urban space since 2016, which seems to be several years ahead of previous projects. The reason: “The ‘Vision Van’ networks numerous technologies and becomes the central, intelligent element in a fully networked delivery chain. Novel algorithms control the picking and loading of packages, the fully automated loading space management as well as the route planning for the vehicle and the delivery drones,” the company says. The trick here is that the vehicle not only transports the goods; it has its own mini high-bay warehouse inside (see picture).

Drone base vs. decentralized hubs

The best transport drone is useless if it cannot transport anything. In the classic transport sector, centralised or decentralised distribution centres have long been used. Even smaller hubs, where goods can be stored decentrally, are increasingly being taken into account in companies’ logistics planning.

If one refers to the mentioned flight times of the individual drones, a central distribution centre makes little sense in terms of logistical infrastructure. To what extent a decentralized warehouse appears more useful is currently (see examples) being tested in field trials by many CEP service providers and large corporations (Amazon, Mercedes Benz). Whether a centralized drone base or decentralized hubs: a corresponding delivery area will continue to have only a small radius in the future. In addition to the insufficient battery power of the flying drones, the replenishment must also be considered in completely new processes. Whether this type of logistics is also suitable for metropolitan regions must be clarified above all by courts: Air traffic control, insurance cover, the human factor, the current legal situation (see legal situation) and, of course, the lack of infrastructure are important points to be mentioned here.

Conclusion: Customer delivery from the air – the future of logistics?

Today, delivery vehicles of CEP service providers block entire streets because they are forced to park in the second row. In large cities, the congestion is often so great that suppliers often block themselves. This development is exacerbated by customers who demand ever faster deliveries. A redistribution of delivery orders that can be taken over by drones only makes sense for certain goods, however.

The advantages of delivery from the air are nevertheless obvious: the parcel drones are not tied to the road network. Natural barriers are no obstacle for them. Also, urban areas could be approached, with additional efforts. Transport drones allow a decoupling from the classical transport network and central logistics, the consequences of this decoupling we can only speculate about at present. Ultimately, in some cases, roads and railways will no longer be necessary. Nevertheless, drone delivery is certainly not suitable for all goods. However, urgently needed goods such as medicine, food and clothing in areas that are difficult to access or in rural areas in general can be delivered better and faster by drone.

New smart concepts will soon determine how drone technology will be integrated into the prevailing traffic flows. In the future, company computing centers will evaluate the data collected on traffic density, weather conditions or environmental pollution. The informationcomes in part from the drones themselves – from their built-in sensors and cameras. And thanks to the networked infrastructure and the matching drone concept, companies such as Amazon, DHL, UPS and Mercedes Benz may be able to reduce the daily urban traffic jams caused by CEP service providers.

The article was written in editorial collaboration with Torsten Schmitt. Schmitt alias @Pixelaffe calls himself ‘Ge.rd’ – half geek, half nerd. He works as developer, project manager, blogger and consultant and is ‘chief pilot’ at Dronecamp since 2015. In addition, he writes for his blog Pixelaffe.

Additional sources:

Amazon – these five patents can change the world

Also available in Deutsch (German)